The province is proposing a massive overhaul of Ontario’s vast healthcare system, which, if implemented, promises to shakeup how services are planned, delivered and funded in the province.

Dubbed Ontario Health, the new system would do away with the network of 14 Local Health Integrated Networks (LHINs), which individually operate across the province, as well as the six provincial agencies like Cancer Care Ontario and the Trillium Gift of Life Network that supplement the system.

In their place, these services will be organized under the umbrella of Ontario Health Teams, where local healthcare providers, including hospitals, primary care and health centres, can band together into teams to organize health services in their areas.

The government says the move would revamp a “fractured” health system, which has been inundated with rising costs and increasing demand.

“When care is funded in silos, care ends up being delivered in silos,” said the Ford government in a statement. “When providers are asked to partner to work together as one connected team, care will be integrated. Integrated care looks at the whole person, not just the illness. It means patients and their caregivers will have someone to call to help them navigate the system, to answer questions and to understand their circumstances.”

Opponents warn the government’s proposal would cause job losses in the health sector, pointing to the Grand River Hospital’s recent slashing of 40 nursing positions as an affirmation.

“Ontario families remember the disastrous health transformation of the [former premier] Mike Harris era, when hospital beds were closed, hospitals were shuttered, and thousands of nurses were fired,” said Andrea Howarth, leader of the Ontario NDP, at the legislature on February 28.

“Not long ago, the premiere pretended not a single job would be lost. However, just yesterday, the Grand River Hospital in Kitchener announced 40 nurses would be losing their jobs this week due to budget shortfalls.”

The NDP also accused the Ford government of opening the province’s healthcare to “unprecedented levels of private and for-profit health care.”

Local health organizations were more optimistic with the changes, however, with the Woolwich Community Health Centre saying no impacts on service were expected during the years-long transition to the Ontario Teams model.

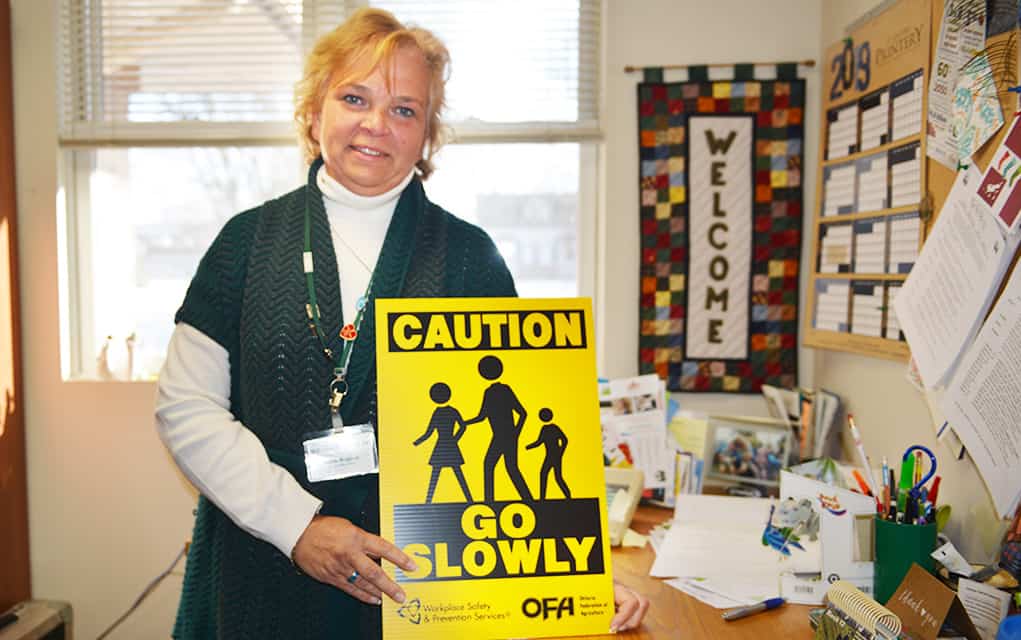

“The community health teams will be a grassroots collaboration of existing health care providers coming together and developing local health delivery plans meeting specific criteria,” explained Rosslyn Bentley, executive director of the St. Jacobs-based organization. “The goal is better coordinated care and patient focused care. The focus is also on front line care and community care. No impact on care delivery is anticipated throughout this transformation.”

Under the current system, the WCHC plans health services in the community together with the Waterloo-Wellington LHIN and other stakeholders. That could mean planning for end-of-life or palliative care ahead of time which in turn alleviates pressure on hospitals, which are often the first points of contact for people in need of healthcare.

“What we do with the LHIN currently, we participate in the healthcare system planning, so both at the regional level and the sub-regional level (Kitchener and Waterloo),” said Bentley. “It’s two-third urban in the Kitchener-Waterloo, and then one-third rural. So of course we feel very aligned with the rural resources and services, so we sit regularly at the planning table with our colleagues from across the region.”

Who will get a chair at the table under the new model is yet unclear, says Bentley, but the change in how healthcare is structured in the province is bound to have an impact on the WCHC’s role.

“It might be the same people, they might have different titles, or it could be different people,” she said. “So then the agenda for us changes to being a little bit more about making sure the rural aspect of care is represented.

“People in rural areas, because they don’t have transportation, and they don’t know what’s being offered sometime, don’t ask for those sorts of services,” added Bentley. “People make do. So we’re very good in communities about coping with what’s not there, and that’s not always fair in a publicly funded healthcare system.”