;

;

;

Next Article

Lady Lancers start soccer season with win and tie

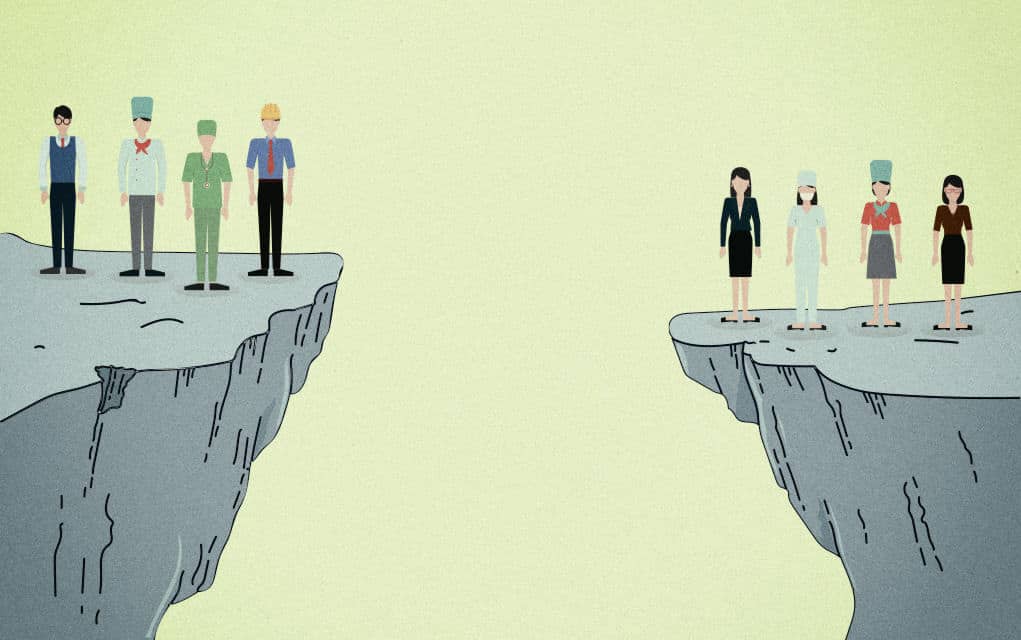

Everyone knows women tend to earn less than men – that much is a fact. Quantifying and explaining the differences en route to eliminating them is the focus of a joint project between researchers at Wilfrid Laurier University and the University of Waterloo. The study takes aim at the fact that women

Last updated on May 04, 23

Posted on Apr 21, 16

4 min read